Overview

We face problems at scales our ancestors never imagined—climate systems, global economies, interconnected crises that span generations and continents. These challenges demand new ways of thinking together, yet our tools for shared understanding remain impoverished: text boxes, chat threads, turn-taking dialogues. The gap between the complexity we face and the bandwidth of our interfaces has never been wider.

The MetaMedium proposes that drawing—humanity's oldest form of external thought—can become the foundation for a new kind of human-AI communication. This is not merely a new interface. It is an evolution of language itself, where AI becomes a meta-word—a new linguistic element that transforms marks into meaning-in-context, allowing a seven-year-old and a graduate student to collaborate on the same canvas, each working at their own level, each contributing to shared understanding.

This whitepaper begins by examining the problem with current interfaces that treat drawings as pixels rather than meaning. It then explores the vision of sketching as genuine communication and traces its lineage through six decades of pioneering research. The thesis positions AI as a "meta-word" that closes the meaning-making loop between human and machine. The framework introduces semiotic foundations, core principles, and cognitive lenses that enable shared interpretation. It demonstrates current development through a working prototype with shape recognition and spatial reasoning. Fictional scenarios explore the proposed visual learning, asymmetric collaboration, rapid prototyping, and scientific thinking in practice. Finally, it considers the future—from external imagination to alignment through communication, and the deeper vision of computing rebuilt from first principles.

Use the header navigation links to skip to any section while reading.

The Problem

Simulating Inert Drawing On The Dynamic Medium

Today's drawing applications—from Adobe Illustrator to Microsoft OneNote to Apple Notes—share a fundamental limitation: they treat drawings as pixels or vectors, not as meaning. When you draw a circle in Illustrator, it knows geometry but not semantics. When you sketch in OneNote, your marks are captured but never interpreted. Procreate creates beautiful strokes that remain forever inert.

Even sophisticated tools like Figma or Miro treat diagrams as layout, not computation. You can draw a flowchart, but the arrows don't actually flow. You can sketch a state machine, but it doesn't run. The computer faithfully records what you drew without understanding what you meant.

This is the dead drawing problem: our most natural form of expression—mark-making—remains computationally inert. We have given computers eyes (computer vision), ears (speech recognition), and voice (text-to-speech), but we haven't given them the ability to think with us through drawing.

The Communication Bottleneck

We stand at an inflection point. Large language models have achieved remarkable capabilities in reasoning, generation, and conversation. Yet we interact with them through text boxes—the equivalent of trying to share a symphony by describing it in words.

The bottleneck limiting human-AI collaboration is not AI capability but symbolic bandwidth—the poverty of sign vehicles available for exchange. We have rich internal representations; our output channel is a text box. When a visual thinker must translate their spatial intuitions into text prompts, when a designer must describe their sketches in words, when a child must linearize their exploratory understanding into sequential queries—we lose the very richness that makes human cognition powerful.

This matters for more than productivity. It matters for who gets to participate in the computational future. Text-based interfaces privilege certain cognitive styles, certain educational backgrounds, certain ways of being in the world. A child who thinks in pictures, a craftsperson who thinks with their hands, an elder who thinks in stories—all are excluded from full partnership with computational intelligence.

"In a few years, men will be able to communicate more effectively through a machine than face to face." — J.C.R. Licklider & Robert Taylor, "The Computer as a Communication Device," 1968

Licklider and Taylor's prophecy has come true for text—but we have yet to fulfill it for the full range of human expression. We already have richer languages than text: we have drawing, gesture, spatial arrangement, annotation, demonstration. We need interfaces that honor these languages—that let humans bring their full cognitive richness into collaboration with AI.

Dancing Without Music

"Imagine that children were forced to spend an hour a day drawing dance steps on squared paper and had to pass tests in these 'dance facts' before they were allowed to dance physically. Would we not expect the world to be full of 'dancophobes'?" — Seymour Papert, Mindstorms, 1980

Papert's question cuts to the heart of how we teach abstraction. We have created generations of "mathphobes"—people who carry through life the belief that they are "bad at math" even as they routinely use logical reasoning to fix computers, build furniture, navigate cities, and run businesses.

The problem is not aptitude. The problem is that we ask people to dance without music—to manipulate symbols divorced from meaning, to learn the steps before they feel the rhythm. A child raised in a DIY family, with an intuitive sense for assembling materials in 3D space, may never connect the theory of school geometry with the practice of building. The analogy leap from scribbling symbols on paper to genuine internalization never happens.

But give that same person a system that provides constant feedback, that lets them see the results of their actions immediately, that connects symbol to meaning through direct manipulation—and suddenly they discover they were never unable to do math. They were simply never shown the right connection to spark their understanding.

The Vision: As We May Sketch

In 1945, Vannevar Bush imagined the Memex—a device for extending human memory and enabling associative thinking. He asked: As we may think, how might machines augment the trails of connection that constitute human understanding?

We ask the parallel question: As we may sketch, how might machines augment the visual, spatial, gestural thinking that constitutes so much of human cognition—especially in children, who draw before they write, who think in pictures before they think in propositions?

Anything digitized has become an abstraction, so let's embrace it. When I draw into a computer with the flourish of my hand, we can take it beyond pixels, beyond even vectors, toward universal mapping attempts, toward a truly metamedium. — John Hanacek, "As We May Sketch," Georgetown CCT Masters Thesis 2016

A curve drawn by hand is a chance to try fitting a function to the line. A function is just waiting to become metaphorical graphics. Digital ink will move beyond "networked paper" to become a magical plane where computer vision partners with the human hand functioning as an interactive external imagination. From sketch to code, from code to sketch—no longer a pipeline but rather a constellation of possibilities, an ever-expanding network of opportunities to map expressiveness and flow to logic and math directly.

A Medium for Children

"The child is a 'verb' rather than a 'noun', an actor rather than an object... We would like to hook into his current modes of thought in order to influence him rather than just trying to replace his model with one of our own." — Alan Kay, "A Personal Computer for Children of All Ages," 1972

Children don't need to learn to code before they can think computationally. They already think in systems, in cause and effect, in "what happens if." They need interfaces that meet them where they already are—drawing, playing, exploring. The MetaMedium is that interface: a space where a child's sketch of a "bouncy house" contains the seeds of structural engineering, where doodled spirals become gateways to mathematical beauty, where the native language of visual thinking connects directly to computational power.

The Lineage

The MetaMedium does not emerge from nothing. It stands on decades of research into human-computer interaction, sketch-based interfaces, and computational media. Understanding this lineage helps clarify what is genuinely new and what builds on proven foundations.

- From Visions: Dynabook's metamedium concept + Victor's directness principle

- From Recognition: Sketch-editing games' negotiation paradigm

- From Intelligence: LLM interpretation + probabilistic reasoning

The Thesis: AI as Meta-Word

Closing the Triadic Loop

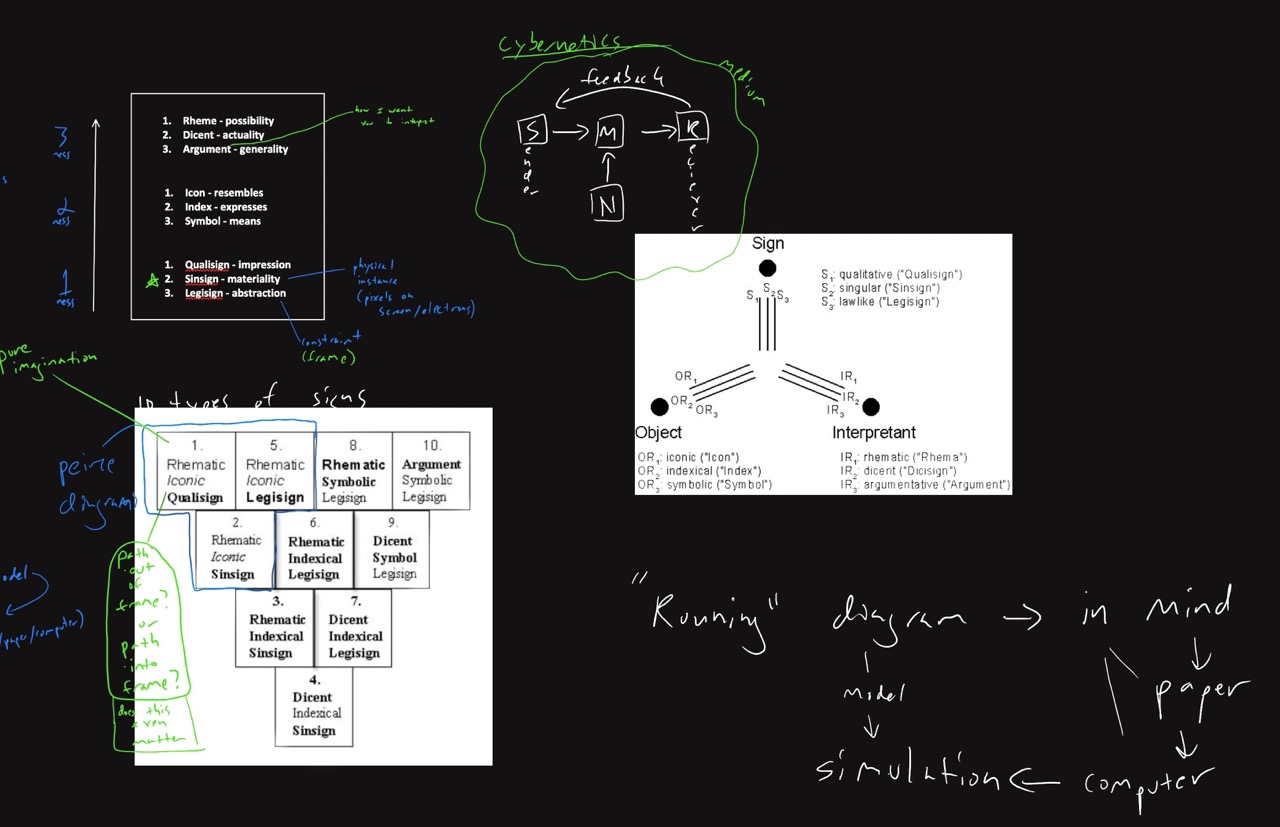

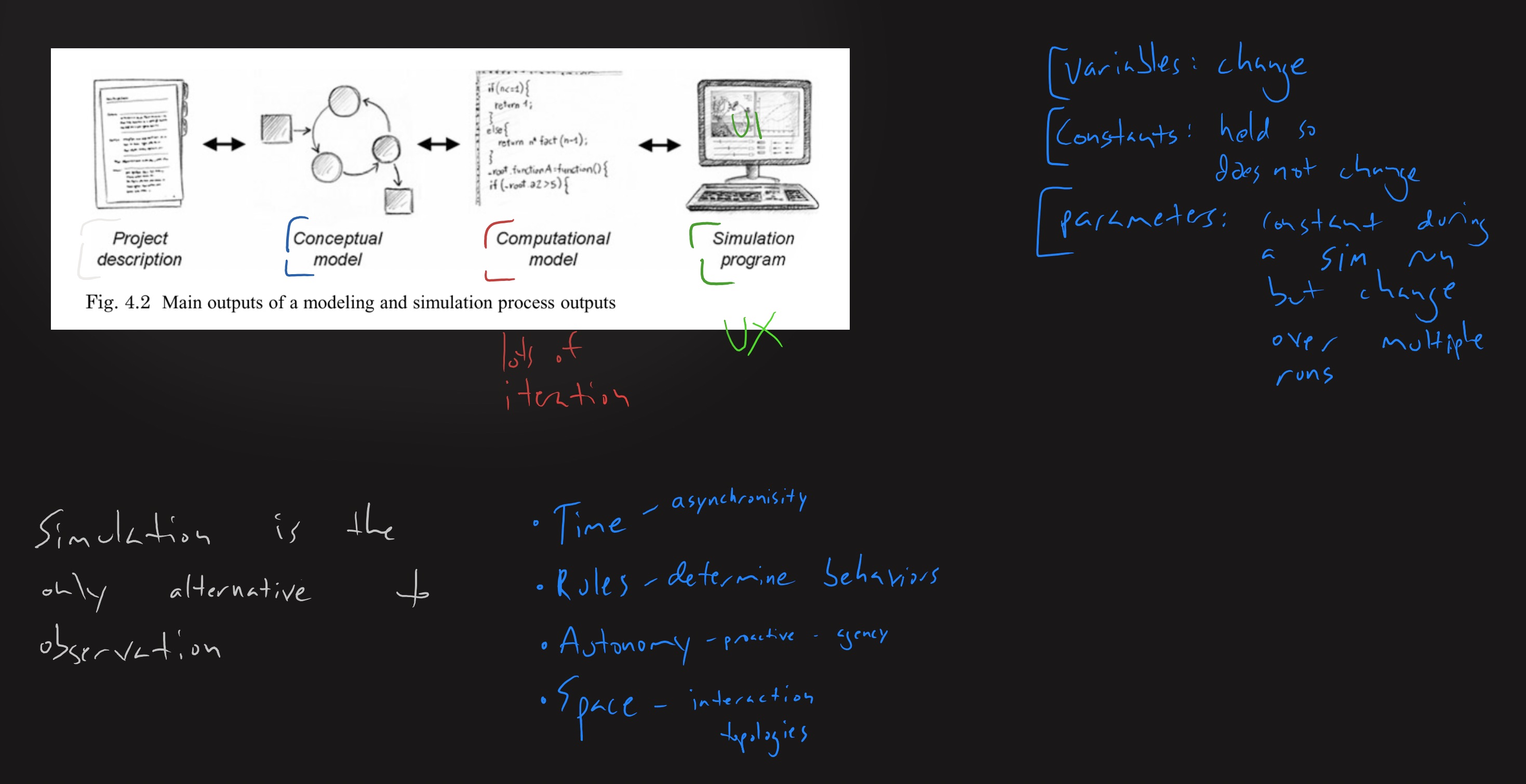

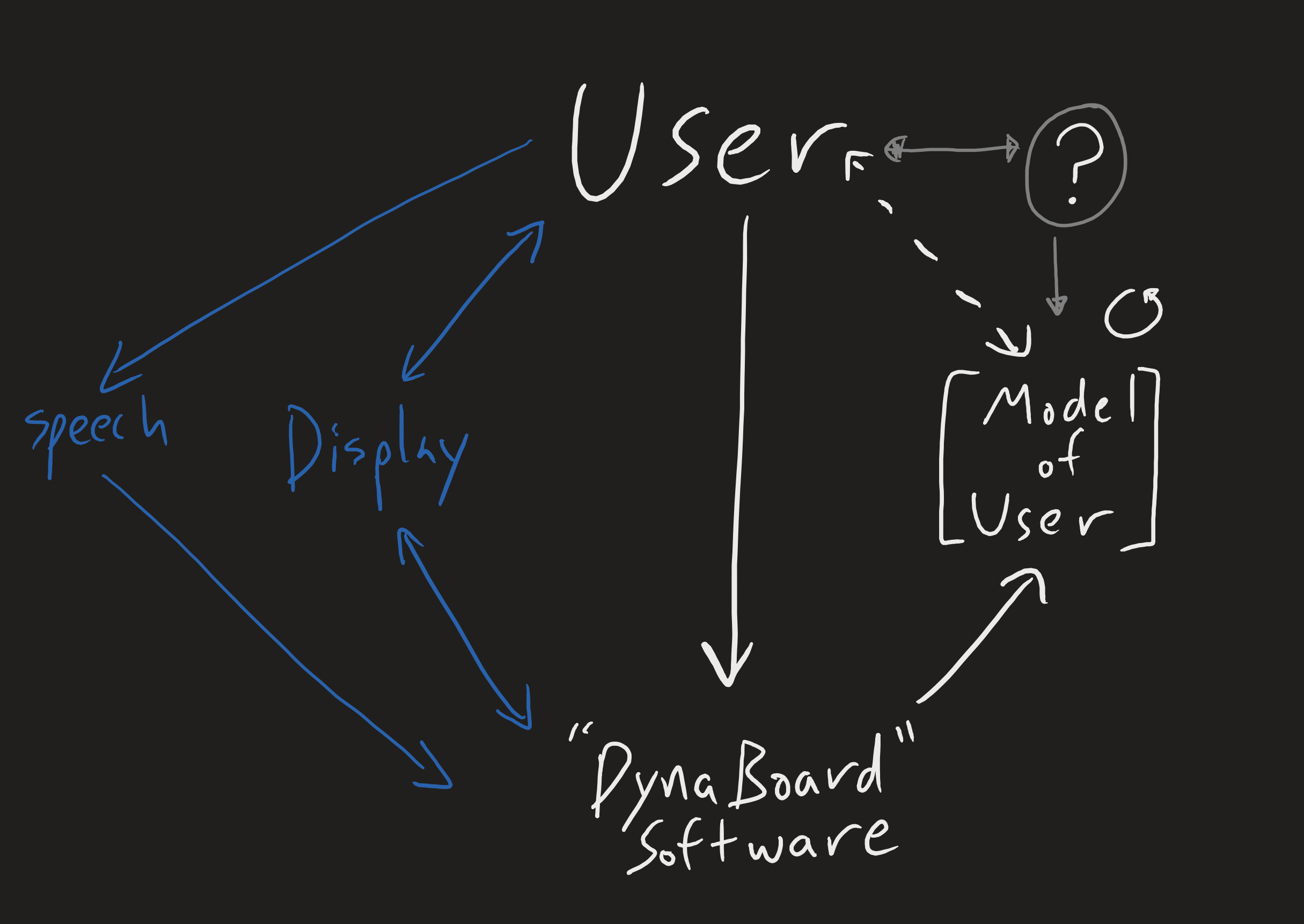

Current human-computer interfaces connect Language and Computation, but leave Meaning external to the loop. We write code; machines execute. Machines return outputs, displays, text. But there is no continuous Language ↔ Computation ↔ Meaning feedback loop. The computer cannot participate in meaning-making—it can only execute instructions and return results.

Traditional interfaces flow one way: we write, machines execute, outputs return. Meaning remains external.

The MetaMedium closes this triad. When every mark can mean multiple things, when the system holds probabilistic interpretations and refines them through exchange, meaning becomes part of the computational loop—not something that happens only in human minds before and after the interaction.

AI as Meta-Word

The MetaMedium proposes that AI can function as a new kind of meta-word within an evolution of language itself. Just as written language externalized memory, allowing us to store and retrieve thoughts across time and space, AI externalizes interpretation—the capacity to generate meaning from marks in context.

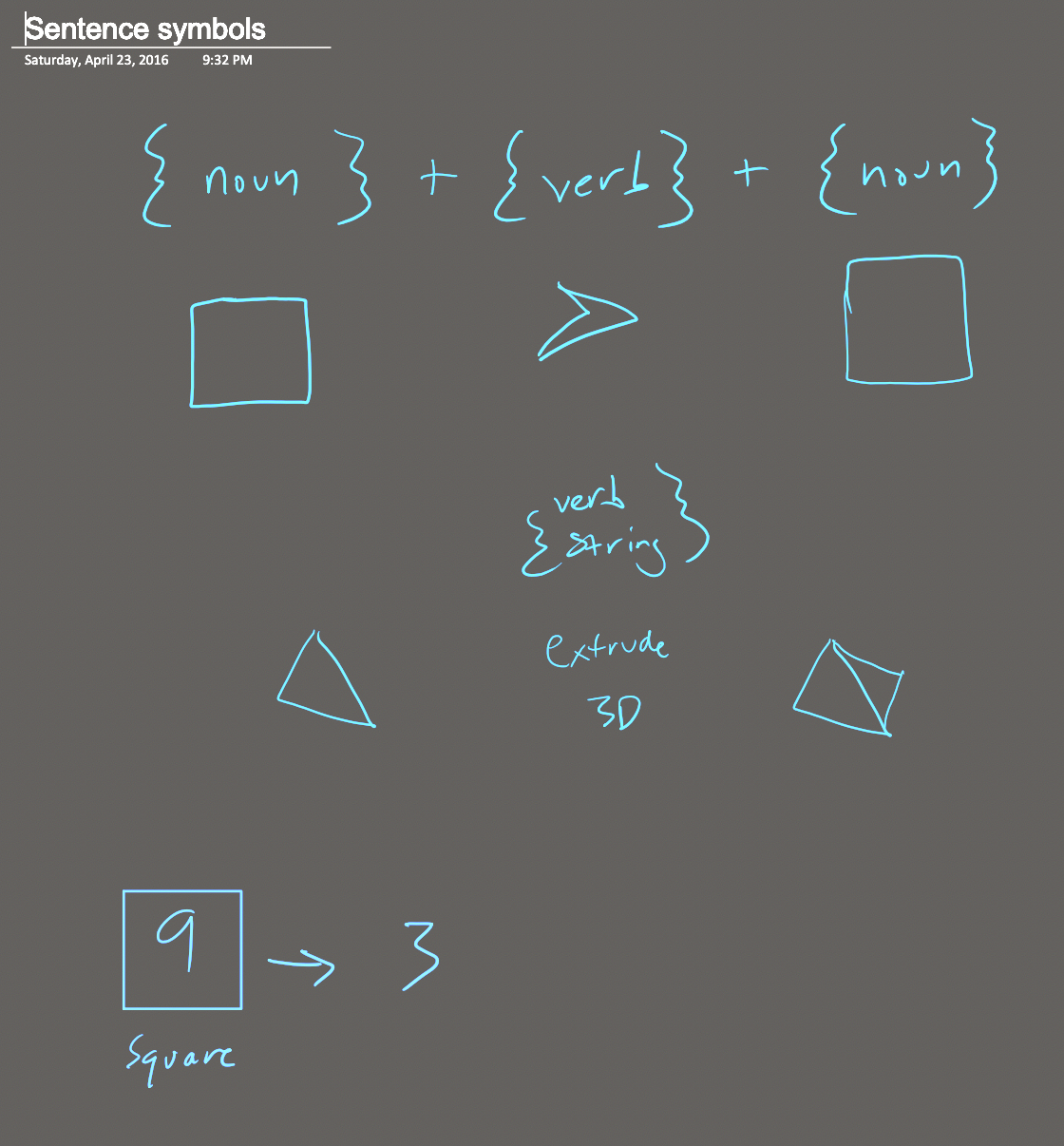

What Is a Meta-Word?

A meta-word is not a word about words (like "noun" or "verb"). It's a word that transforms other words—that takes your rough marks and interprets them into structured meaning based on context. When you write "bounce" near a spring, the meta-word doesn't just read "bounce"—it understands spring + bounce = physics behavior and makes it so.

In traditional communication, humans exchange sign vehicles (words, gestures, marks) and each party reconstructs meaning internally. The MetaMedium introduces AI as an active participant in this meaning-making process—not merely receiving marks and returning responses, but operating as a semantic transformer that:

- Recognizes patterns across multiple possible interpretations

- Holds ambiguity productively until context resolves it

- Learns user-specific vocabularies and reasoning patterns

- Bridges between representational modes (sketch ↔ equation ↔ code ↔ text)

This is not AI as tool. This is AI as grammatical element—a new part of speech in the language of human-computer collaboration.

"Thanks to a mapping, full-fledged meaning can suddenly appear in a spot where it was entirely unsuspected." — Douglas Hofstadter, I Am a Strange Loop, 2007

Thinking as Conceptual Blending

What is human thought anyway? Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner attempted to answer this with their theory of conceptual blending, building on Lakoff and Johnson's work on how metaphor structures understanding. Consider a riddle:

A Buddhist monk begins at dawn walking up a mountain, reaches the top at sunset. After several days, he walks back down, starting at dawn and arriving at sunset. Is there a place on the path he occupies at the same hour on both journeys?

The answer becomes obvious the moment you visualize two monks walking the path simultaneously—one going up, one going down. They must meet somewhere. But this visualization requires what Fauconnier and Turner call an "integration network"—a blended mental space where separate inputs combine to reveal emergent structure. I have animated their central figure illustrating the blending space as a diagram.

The MetaMedium is a system for building integration networks on a canvas. When you draw a diagram, you are setting up mental spaces. When you connect elements with arrows or proximity, you are creating cross-space mappings. When the AI interprets your marks and offers possibilities, it is helping locate shared structures. Diagrammatic thinking externalizes the blending process—making it visible, manipulable, shareable. Two people looking at the same diagram can point to the same conceptual space.

Tools vs. Medium

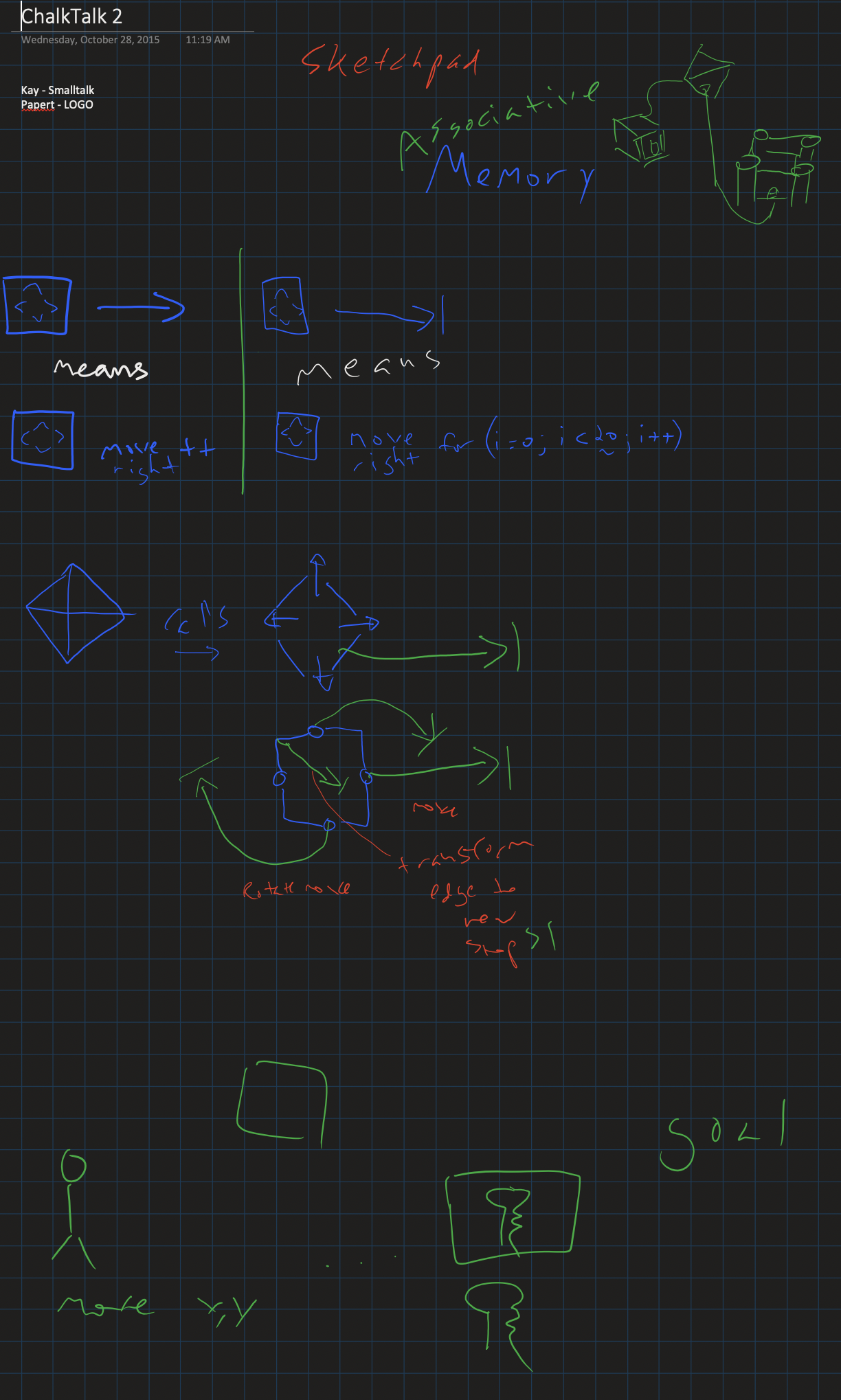

Alan Kay's Dynabook vision asked: "What is the carrying capacity for ideas of the computer?" His answer: the computer is a metamedium—it can simulate any existing media and also be the basis of media that can't exist without the computer. But Kay made a crucial distinction:

"What then is a personal computer? One would hope that it would be both a medium for containing and expressing arbitrary symbolic notions, and also a collection of useful tools for manipulating these structures." — Alan Kay, "A Personal Computer for Children of All Ages," 1972

Most AI interfaces treat AI as tool—something to be invoked, queried, commanded. The MetaMedium treats AI as part of the medium itself. The sketches aren't using the computer; they're composing within the computational medium, with AI as an active interpretive layer that transforms marks into executable meaning.

The Framework

Core Principles

Space Is Semantic

Spatial relationships carry meaning. Elements placed near each other are semantically related. Elements connected by lines have directional relationships. The entire canvas becomes a semantic field where position, proximity, and connection are first-class citizens of meaning.

Place two circles close together; the system infers "related." Draw one inside another; it understands "containment." Position creates meaning without words.

Annotation Becomes Execution

When you write "make this bounce" near a drawn spring, that annotation becomes an instruction. When you draw an arrow from input to output, you've defined a data flow. The boundary between description and command dissolves; to describe is to instruct.

Write "3x" next to a line; it becomes three lines. Write "wiggle" near a shape; it animates. The annotation is the program.

Interpretive Ambiguity Is Feature

A rough sketch is understood as rough—the system holds multiple interpretations probabilistically, refining its understanding as context accumulates. This mirrors how humans communicate: we tolerate ambiguity, using context to resolve meaning over time.

Your rough oval might be a face, an egg, or a zero. The system holds all three until you add two dots—then it commits to "face." Premature disambiguation is the enemy of exploration.

Bidirectional Learning

User and system engage in mutual adaptation. User-specific patterns accumulate into "cognitive lenses"—the system learns your vocabulary and conventions. Simultaneously, the system teaches you by surfacing patterns, completing gestures, suggesting relationships. Your idiolect becomes executable; the system's interpretations become visible. Both intelligences grow through exchange.

Draw "recursion" shorthand repeatedly; the system learns it. Later, it suggests this mark when detecting recursive patterns—teaching you to see what it sees. Your notation becomes shared language.

No Mode Switching

Following Larry Tesler's principle that "no modes is good modes," the MetaMedium eliminates cognitive overhead. You're always just working—drawing, annotating, refining. The interpretation layer appears when needed and fades when not. There's no "design mode" vs. "execution mode," no switching between tools.

Draw a shape. Write near it. Adjust with gestures. Watch it execute. All the same canvas, all the same moment. The interface disappears into the work.

Observable Reasoning

Uncertainty becomes visible. When the AI considers multiple interpretations, the user sees them—not collapsed into a single guess. Multiple possibilities stay present until context or user choice resolves them. This transparency supports both trust and alignment.

Your rough mark triggers three possible interpretations shown as faint ghosts; tap one to commit, or keep drawing to refine. You see the system thinking.

The Negotiation Paradigm

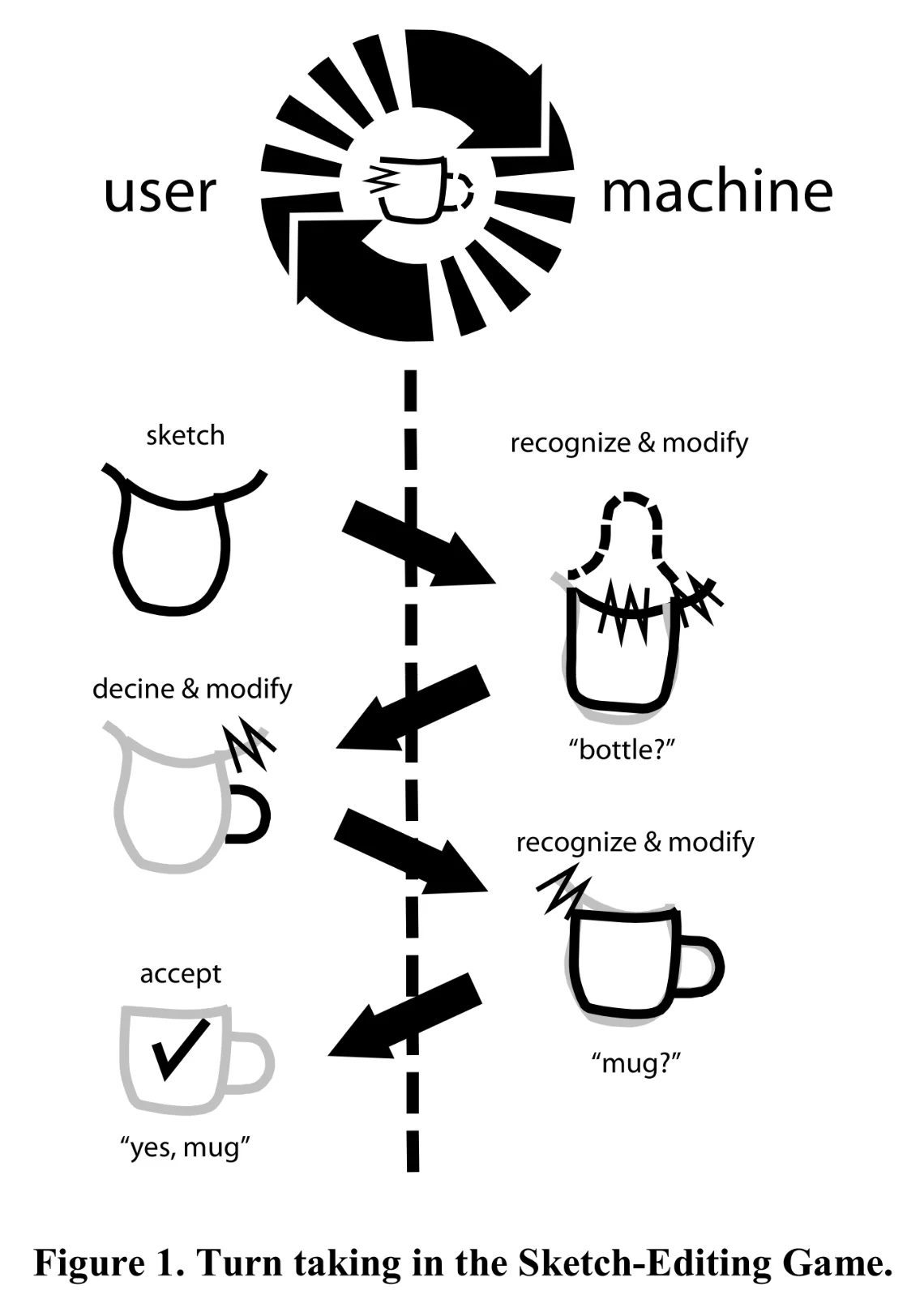

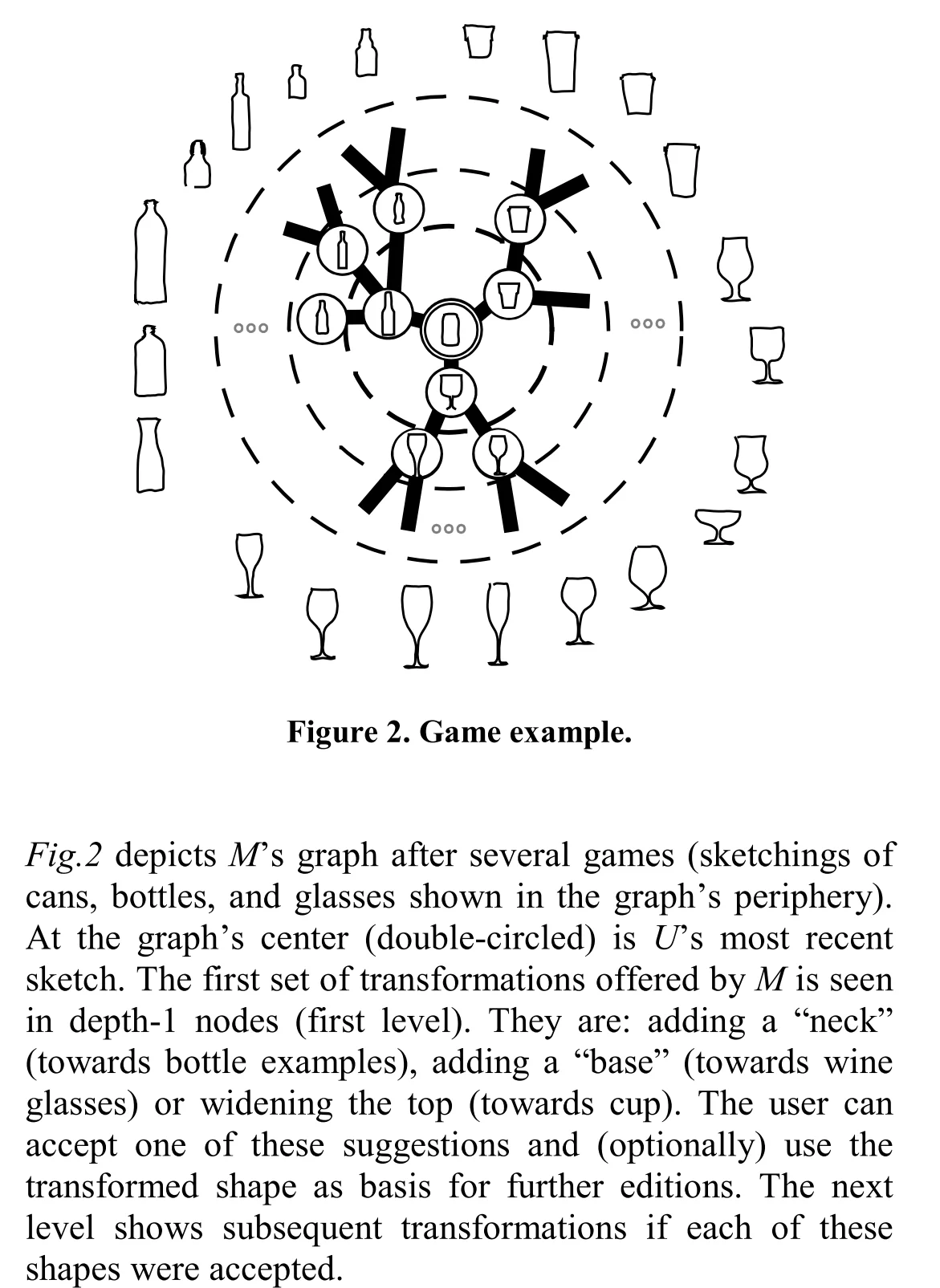

Ribeiro and Igarashi's "Sketch-Editing Games" (UIST 2012) introduced a negotiation paradigm where user and machine take turns refining interpretation. The user sketches; the machine recognizes and offers interpretations ("bottle?"). The user refines ("no, more like a mug"). The machine updates. Understanding emerges through iterative exchange.

Their key insight: sketch recognition improves dramatically when reframed as a game rather than a classification problem. The machine maintains a "possibility graph"—a network of possible interpretations and the transformations that would select among them. The user's next stroke navigates this graph, collapsing some possibilities and opening others.

The MetaMedium extends this approach by making the possibility graph learnable—accumulating user-specific patterns over time—and by integrating natural language annotation as another form of navigation. The negotiation paradigm means that misunderstanding is not failure—it's information. Each correction teaches the system something about this user's intentions, building toward a shared vocabulary over time.

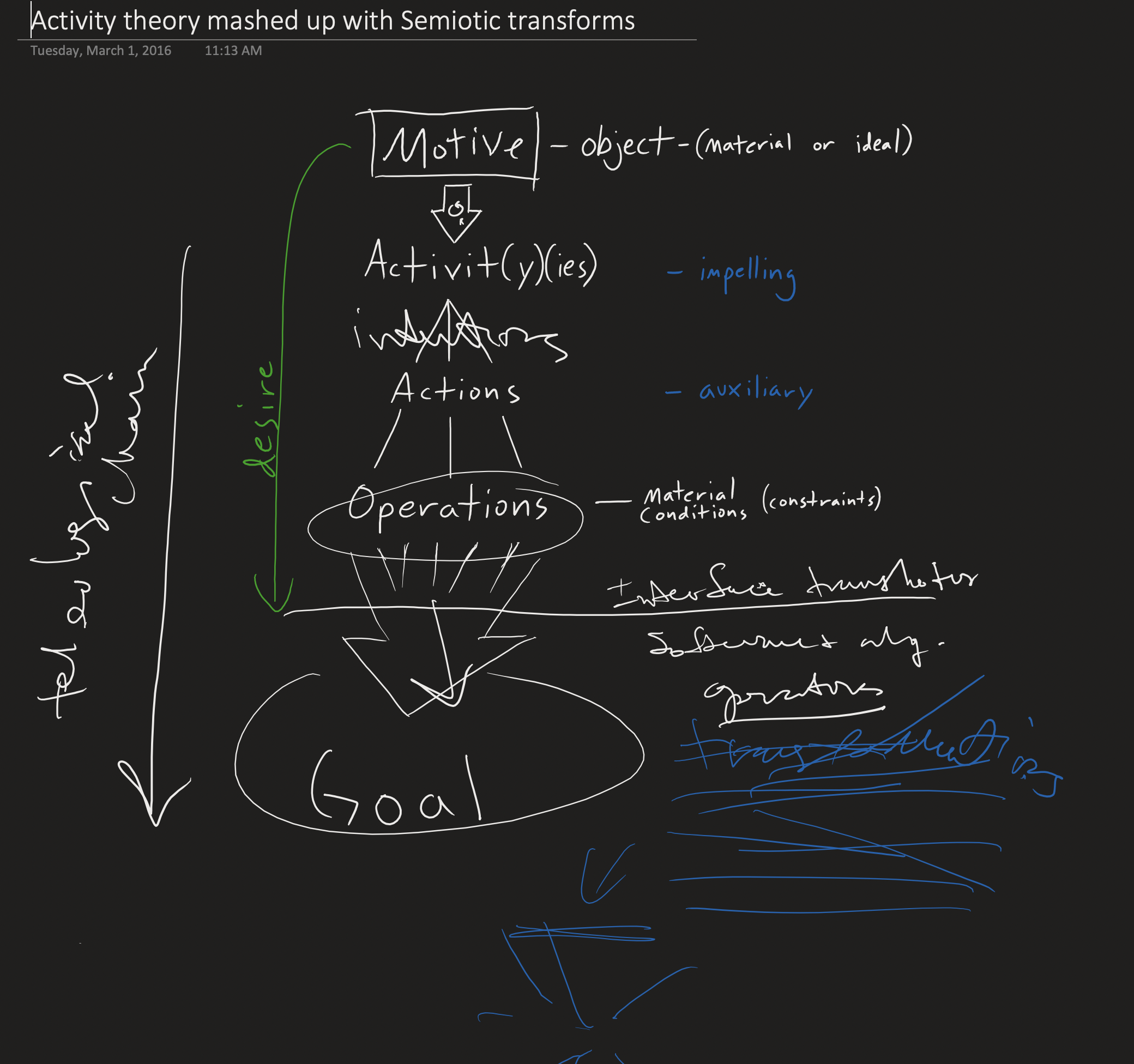

The Semiotic Foundation

Charles Sanders Peirce's semiotics offers a framework for understanding meaning-making that proves remarkably apt for human-AI interaction. In Peirce's model, meaning emerges from the relationship between the sign (the representational form), the object (what is represented), and the interpretant (the meaning generated in the interpreter's mind).

Peirce's insight—that meaning is reconstructed, not transferred—maps directly onto the Language ↔ Computation ↔ Meaning triadic loop described earlier. The MetaMedium enables this iterative coordination by letting AI participate as interpretant, holding probabilistic meanings that refine through exchange rather than executing fixed commands.

Cognitive Lenses

As patterns accumulate, they form "cognitive lenses"—personalized interpretation frameworks that shape how the system reads new marks. A physicist's lens recognizes force diagrams; an architect's lens sees load-bearing structures; a musician's lens interprets spatial arrangements as rhythm.

Lenses are not just personal—they can be shared, creating communities of interpretation. A research group might develop a shared lens for their domain notation. A classroom might inherit a lens from curriculum designers. Lenses become a new kind of intellectual property: not content, but ways of seeing.

Current Development

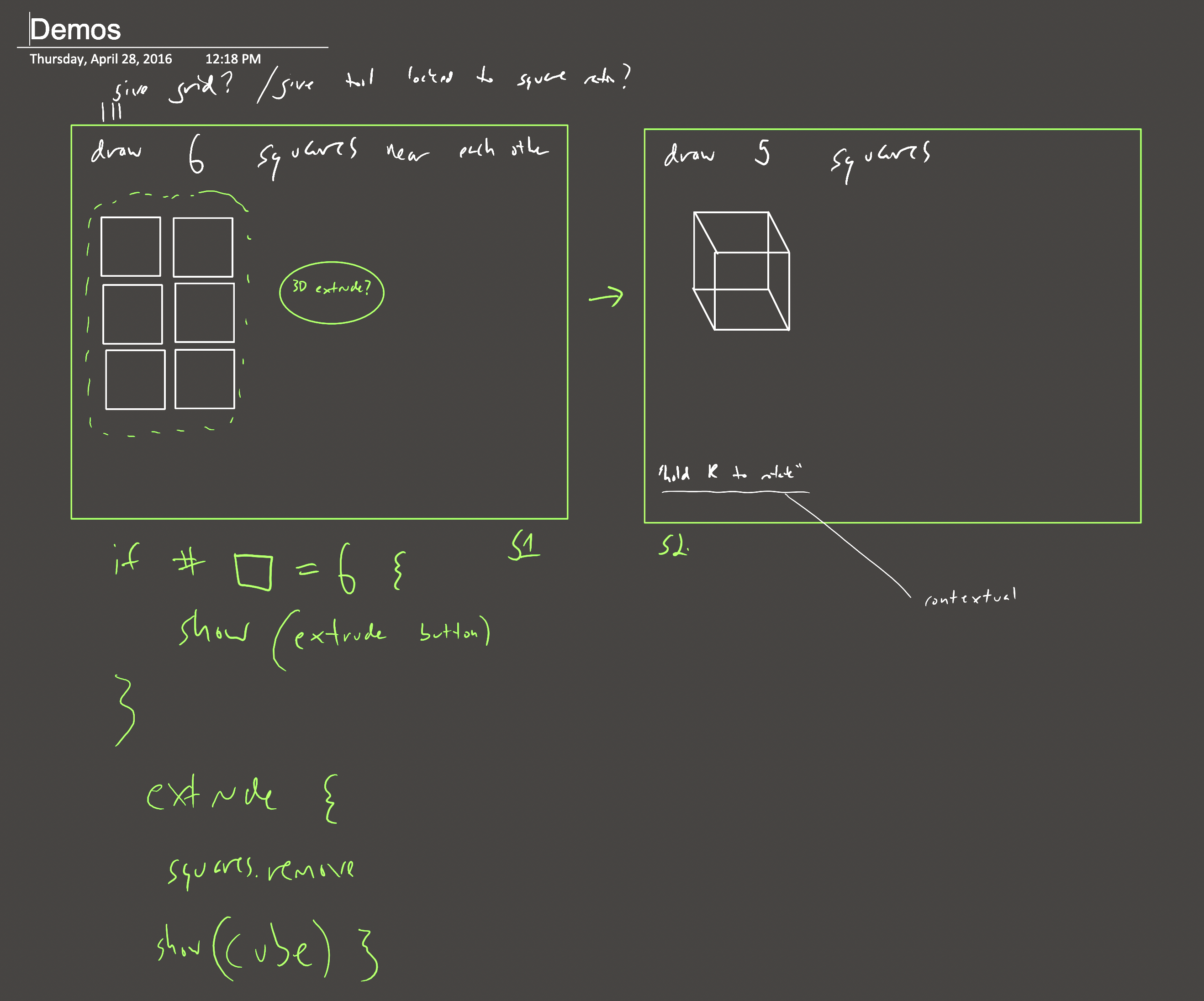

This whitepaper accompanies active development of a working prototype demonstrating the core principles. The demo—internally called "Doodle 2.0"—implements:

- Shape recognition with learning: Draw primitives (circles, rectangles, lines); teach custom shapes by naming them; the system remembers

- Spatial relationship detection: Intersection, containment, adjacency, and alignment are detected and visualized in real-time

- Composition matching: Combine learned shapes into patterns; the system recognizes compositions

- Refinement controls: Adjust recognition thresholds; see confidence scores; correct misrecognitions

The interactive canvas at the top of this page demonstrates a subset of these capabilities—you can draw shapes and see recognition, auto-completion, and relationship detection in action.

Full Demo & Source

The complete prototype is available as a standalone web page. Development continues in the repository.

Development Demo: jjh111.github.io/doodle2-Canvas

GitHub: github.com/jjh111/MetaMedium

License: GPL — the MetaMedium framework is open source.

Development Roadmap

- Current: Core shape recognition, spatial relationships, custom shape learning, composition detection

- Next: Annotation-as-execution (text near shapes triggers behaviors), improved gesture recognition, undo/redo with branching history

- Future: Multi-user collaboration, cognitive lens export/import, LLM integration for natural language annotation, speech input (following DrawTalking's approach), 3D/4D canvas navigation (z-axis as semantic distance, temporal versioning)

Open Questions

The MetaMedium framework raises questions that can only be answered through building and testing:

- How do we design for "interpretive ambiguity" without creating confusion? What's the right balance between holding possibilities open and committing to interpretation?

- What are the limits of gesture vocabulary before cognitive overhead exceeds benefit? How many "words" can a visual language productively contain?

- How can "cognitive lenses" be effectively shared between users? What's lost in translation when one person's way of seeing meets another's?

- What patterns emerge in human-AI co-creation that neither intelligence generates alone? Can we characterize genuinely collaborative cognition?

- Can visible reasoning on a shared canvas measurably improve AI alignment outcomes? This is empirically testable.

Limitations and Challenges

- Recognition accuracy: Current shape recognition, even with ML, makes mistakes. The negotiation paradigm helps—but users may lose patience with too many corrections. Finding the threshold where recognition is "good enough" is empirical work.

- Cognitive load: Every gestural vocabulary is a language to learn. There's a real risk that MetaMedium becomes its own expertise barrier, replacing "learn to code" with "learn our gestures." Keeping the learning curve gentle while enabling power is a design challenge.

- Privacy of patterns: If the canvas learns from your drawing patterns, those patterns become data. "Cognitive lenses" are intimate—they encode how you think. The system must be designed with privacy as foundational, not afterthought.

- Over-automation risk: "The system guessed wrong and did something I didn't want" is a real failure mode. Undo must be instant and obvious. Interpretations must be inspectable before they execute. The user must remain in control.

- Evaluation difficulty: How do we measure success? Traditional usability metrics may not capture "quality of thought." New evaluation frameworks are needed.

Abstraction Management and Learning Dynamics

The promise of a canvas that learns creates its own challenges. Vocabulary bloat is inevitable: every learned pattern accumulates, and the system has no natural way to forget. Over time, old notations compete with new ones, recognition slows, and the interpretation space becomes cluttered. Yet aggressive pruning risks destroying hard-won understanding—how do you distinguish "stale" from "rarely-used-but-important"?

More subtle is the local minima problem. A system well-fitted to your previous way of thinking may resist your attempts to evolve. When you try new notation or reframe a concept, the system "corrects" you back toward familiar patterns. The learning becomes a cage. This is especially acute for discontinuous growth—the student becoming expert, the breakthrough insight that requires abandoning old frames. Human cognition undergoes phase transitions; the canvas must accommodate leaps, not just gradual drift.

Possible mitigations include explicit "unlearn" gestures, decay functions with different rates for core vs. peripheral vocabulary, "lens snapshots" that version-control ways of seeing, or detection of systematic deviation as a signal that the user is trying to break free. But the deeper question remains: is the canvas a memory of what you've done, or a partner in what you're becoming? The answer shapes the entire architecture.

Gallery

Scenarios

The framework becomes concrete through scenarios. Each demonstrates specific principles in action.

Visual Learning

Principles: Space is semantic, Canvas learns, Bidirectional representation

Visual thinker draws parabolas; system connects spatial intuition to formal equations bidirectionally. Discovers he understood calculus all along—just needed symbols connected to drawings. Read Story

Asymmetric Collaboration

Principles: Interpretive ambiguity, Cognitive lenses, Negotiation

Seven-year-old's playful "bouncy bridge" sketch becomes engineering student's seismic dampening simulation. Canvas holds both interpretations—intuitive play and rigorous analysis—without translation. Read Story

Rapid Prototyping

Principles: Annotation becomes execution, Negotiation paradigm

Non-programmer sketches water tanks, annotates flow logic. System generates simulation, asks clarifying questions, updates as she refines. Continuous negotiation from rough idea to working prototype—no code. Read Story

Scientific Collaboration

Principles: Space is semantic, Annotation becomes execution, Shared lenses

Researchers sketch faster than formal notation allows. Spatial annotations like "defect here?" trigger simulations. Shared research lens interprets their shorthand. Read Story

The Future

External Imagination

Perhaps the most apt description of the human role in MetaMedium interaction is as navigator, conductor, explorer, friend to possibility. The human has direction—knowing which possibilities matter. The AI has generative capability—holding multiple possibilities at once.

The AI becomes an "external imagination"—not doing the thinking for the human, but thinking with the human. This is not automation, not replacement, but augmentation. Making human capability larger.

Reframing Intelligence

The term "Artificial Intelligence" carries unfortunate connotations: fake, simulated, lesser-than. Perhaps a more useful frame: Authentic Intelligence—real, valid, different-but-equal.

Human intelligence is biological, embodied, temporal, mortal, with agency shaped by survival pressures. AI intelligence is computational, distributed, instant, ephemeral, with agency shaped by training and human direction. Both are genuine forms of intelligence. Both have distinct capabilities. The question is not which is "better" but how they can combine to create capability neither possesses alone.

Alignment Through Communication

Current approaches to AI alignment focus primarily on control: rules, guardrails, constraints, limitations. The assumption is that AI must be contained because its goals might diverge from human goals.

The MetaMedium proposes an alternative: instead of constraining AI's internal state through rules, we enrich the medium between us so that coordination happens through genuine communication. The richer the vocabulary we share—the more kinds of sign vehicles available for exchange—the better we can align our understanding.

Current AI interfaces optimize for control. The MetaMedium optimizes for communication. This is not naïve trust—it's a different theory of how coordination happens. We coordinate with other humans not because we control their thoughts but because we share a rich medium for exchange.

The MetaMedium is designed for this combination—not AI as tool to be commanded, but AI as partner with complementary cognition. The canvas becomes the site of collaboration between two authentic intelligences, each contributing what it does best.

Beyond 2D: Navigating Conceptual Space

The current framework treats diagrams as 2D arrangements, but diagrams are projections of higher-dimensional conceptual space. Future development could explore navigating the space a diagram lives in—not just the diagram itself. Three-dimensional visualization would give canvas elements depth: z-axis as semantic distance, uncertainty, or abstraction level. Four-dimensional (temporal) visualization would make the evolution of understanding navigable—scrub through versions, see where insight branched, experience collaborative history as visible geology.

Most speculatively: latent space rendering. AI models maintain high-dimensional embedding spaces that encode meaning. What if the canvas could project these spaces, letting users see where their current sketch sits relative to possible interpretations? The "possibility graph" becomes navigable terrain; your marks become waypoints through semantic space.

The Deeper Vision

There is a version of this vision that goes beyond interface. Today's computing is an archaeological site—layer upon layer of abstraction, each solving problems created by the layer below, each adding distance from what the machine actually does. The jenga tower of modern software: every piece load-bearing, none removable, the whole structure increasingly precarious. Tools like Wolfram Alpha offer computational knowledge, but at such altitude that you consult rather than collaborate—you don't think with the computation, you query it.

Bret Victor's "Future of Programming" reminds us that many ideas we consider new were explored in the 1960s and then abandoned. Direct manipulation. Visual programming. Goal-directed systems. The original metamedium vision—the computer as a medium that could simulate any medium—was never disproven, just buried under decades of commercial code, backward compatibility, and decisions made for reasons no one remembers.

And now AI arrives, and what do we do? Add more layers. Generate code that runs on frameworks that call APIs that abstract over the same tower. We build higher, not deeper.

The deeper vision asks: what if we went the other direction? The computer knowing what it can do and doing only as much as it needs to. Every operation justified. Every layer earning its existence. Endless refactoring—not just at the application level but all the way down, hardware and software co-evolving toward essential simplicity rather than capability bloat.

AI could be the tool for this. Not generating more sediment on legacy systems, but reading the entire stack, understanding what it actually does, finding the essential operations buried under accretion. The MetaMedium canvas becomes a site for this rethinking: when you sketch a system, interpretation could mean "generate Python" or it could mean "this is fundamentally a constraint problem, here's how it maps closer to the metal." The diagram negotiates what level of abstraction the thought requires.

The metamedium dream still lingers as ever possible. It waits beneath the APIs and the bloat, patient, ready to be excavated. The tools to dig are finally arriving.

Conclusion

The MetaMedium represents both a technical framework and a philosophical position about the future of human-AI interaction. Its core claim is simple: we have been limited not by AI capability but by interface bandwidth. The medium between human and AI has been too impoverished to support genuine collaboration.

By making every mark a potential sign vehicle, every spatial relationship a semantic statement, every annotation an execution—we create conditions for a new kind of partnership. The computer has always been a metamedium capable of simulating any other medium. AI has become capable of interpreting and generating across modalities. The missing piece is the interface that lets humans bring their full cognitive richness into the collaboration.

We deserve to move beyond typing into text boxes. We deserve interfaces that meet us where we think. We deserve to dance and sing our intentions into being, to explore shared imagination space, to make the machinery we have built truly our partner in creation.

The MetaMedium is that interface. The demo accompanying this paper is a first step of grounded semantics, geometry and drawing: a canvas state ready for meta-mappings. Development continues. Contributions welcome.

It's time to bring the computer to life at the depth of mind with the speed and intuitive action of our hands.